Designed By/Courtesy of QPR Poster Fraggy

-

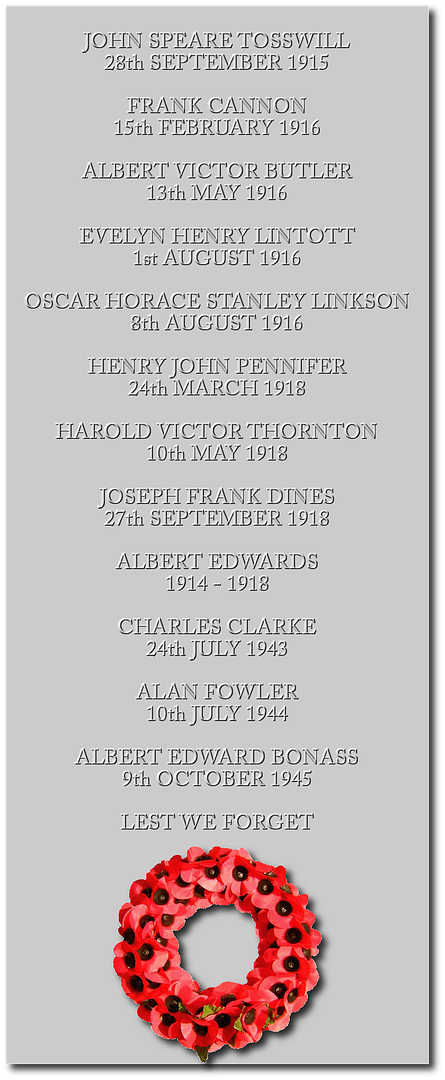

Courtesy of HaQPR1963 Who Designed This Memorial

-

Some Previous Pieces

- Further Details about The Football Battalion

- Henry Winters/The Telegraph: The Football Battalion

- IndyRs "We Will Remember Them"

- QPR Support Poppy Appeal

- Help For Heroes

- From The Bushman QPR Photo Archives

(Obituaries: Found and Posted by Haqpr1963)

![[image] [image]](http://i570.photobucket.com/albums/ss147/hwallen/j_tosswill.jpg)

TOSSWILL, John ‘Jack’ Speare

72726 Corporal, Northern Signal Service Training Centre, Royal Engineers

Died UK September 28, 1915 Age 25

Remembered with honour at Eastbourne (Ocklynge) Cemetery Grave UA250

‘Jack’ Tosswill was born in Eastbourne in 1890. His footballing career started at Eastbourne Borough before moving on to nearby Hastings and St. Leonards, next was Aberdare Athletic, Tunbridge Wells Rangers and then Maidstone Utd. Bigger clubs then followed and he joined QPR (Played 3, scored 1) before moving to Liverpool where he only managed 11 games and scored one goal for the reds. It was from Liverpool that Southend acquired him in 1913 with who he stayed for one season before moving on to Coventry City before the war ended the footballing calendar.

He enlisted in his home town of Eastbourne and for at least some of his time with the military he served with the Royal Engineers Signal Depot based at Dunstable. The signal training services taught the ever improving art of communications, something that had been found to be woefully lacking in the early days of the war. As a training centre they would have taught all forms of signal work such as semaphore, lamps, telephone line laying and the newly utilised wireless. Tosswill was taken ill whilst the unit was based at Southampton, possibly awaiting to be shipped overseas, he was forced to have an operation but unfortunately later succumbed to its effects. He was buried close to the convalescent home in his native Eastbourne.

THE ORIGINAL BLUE ARMY

by Steve Newman

![[image] [image]](http://i570.photobucket.com/albums/ss147/hwallen/-012.jpg)

Deaf footballer dies from operation

Saturday, October 2 – 1915

A likeable fellow, somewhat eccentric, deaf, and a good-class footballer. That is how one might sum up Corporal J.S. Tosswill, whose death is announced this morning. His ear deficiency used to cause some curious happenings in football matches, for he was not able to hear the referee’s signal, and oftimes was seen to proceed to score goals what time the crowd and other players were waiting to take a free kick! Poor Tosswill (writes “Bee”) was a bit of a wag, and his letters to me were always novel and interesting. He was with Liverpool but for a short time, afterwards proceeding to Coventry City. He was brought from Queen’s Park Rangers, and learnt his game with Tunbridge Wells Rangers. On the outbreak of war he joined the R.E. section, and was soon made a corporal.

A capital cricketer, he played for a time with Stanley.

His death took place this morning as a result of an operation at Eastbourne.

(Liverpool Echo, 02-10-1915)Frank CANNON

![[image] [image]](http://i570.photobucket.com/albums/ss147/hwallen/frankcannon1of1-1.jpg)

Frank Cannon

Company Serjeant Major 14982, 11th Battalion, Essex Regiment.

Killed in action: Tuesday, February 15th 1916, aged 32.

Buried: Potijze Burial Ground Cemetery, Ypres, West-Vlaanderen, Belgium. Ref. H. 10.

Born, lived and enlisted in Hitchin.

As with a number of the men on the Pirton War Memorial, Frank’s connection to Pirton is not immediately obvious. In fact, it was not until his connection to West Mill was discovered that Frank’s listing on the Village War Memorial was explained - West Mill lies near Ickleford and adjacent to Oughtonhead Common and the River Oughton and lay within the Pirton parish boundary.

Frank was born on November 8th 1885 in Hitchin and it is the Hitchin records that provide most of the following information.

His parents were John and Martha Cannon, who were born in Hitchin and Therfield respectively. The 1891 and 1901 censuses identify nine children; three girls and six boys, all born in Hitchin. They are named below1. The 1911 census does not add any more names, but gives the total number of children as thirteen and sadly records that five had died.

In 1891 and 1901 the family was living at 14 Church Yard, Hitchin. John (senior) was listed as a grocer in 1891 and then later as gardener and fruiterer. By 1911 most of the family, including Frank, had grown up and left home. The remaining family had moved to 16 High Street, Hitchin; John (senior) now recorded as a fruiterer and nurseryman, with his wife, John (junior), Annie and Ralph all listed as assisting in the business.

It is not clear when Frank left home, but after leaving school he worked in one of Hitchin’s firms of solicitors as a clerk, in fact for Mr Francis Shillitoe the coroner. He was a keen swimmer and diver and also played football for Hitchin Town. He was described as a “dashing player and good dribbler with a fine shot” and he had a County Cap – meaning he was selected to play at least five times. Queen's Park Rangers spotted him and he signed for them in April 1907, although he continued his ‘day job’. He played, and scored, for them against Manchester United in the 1907/08 Charity Shield. The match was played between the Football League champions (Manchester United) and the Southern League champions (QPR), the score was one all, so it was replayed and Frank also played in that game which Manchester United won four nil.

In April 1908, playing centre forward, he scored three goals against West Ham; that must have impressed them because by 1909 he had been persuaded to transfer to them, where oddly he was known as ‘Fred’. It was about this time that he married a young woman called Violet Maud, who was born in Potters Bar, and they moved into 87 Walsworth Road. He debuted for West Ham against New Brompton on January 1st 1910 and in his next game, against Norwich, he scored. That was to be his only goal and after only four appearances, all in January, he left the club. Their daughter Margaret Grace was born later in 1910 and he must have continued playing, because in the 1911 census, when he was boarding with his wife and daughter in the home of George and Annie Eve, 107 Gillingham Road, Gillingham, Kent, his occupation was given as ‘Nurseryman’s son working on nursery and professional footballer’. In fact he went on to play for Gillingham, then Colebridge - located in the Potteries - and finally for Halifax in Yorkshire.

After his return to Hertfordshire, his name appears in connection with the war, in the Parish Magazines of September and October 1914 and by then he and Violet had three children. So it was some time after 1911 that he returned to Hertfordshire, moving to West Mill and taking on a smallholding. Both magazines record him as serving in the Bedfordshire Regiment and the Hertfordshire Express of November 14th 1914 lists him as one of the men of a local rifle club who had enlisted. All the men from the rifle club seem to be from Pirton and by that time Frank had been transferred to the 11th Service Battalion, Essex Regiment and held the rank of serjeant. We know from his Commonwealth War Graves Commission records that he later became Company Serjeant Major.

The 11th Essex was a service battalion – a battalion created specifically for the duration of the war. It was formed at Warley in September 1914 as part of K3 – Kitchener’s third army, and was attached to 71st Brigade in the 24th Division. The following January (1915) they were moved to Shoreham and then to billets in Brighton. In March they returned to Shoreham and then in June moved again, this time to Blackdown Barracks, Deepcut, Camberley, Surrey. They were ordered to the Front in August and landed in Boulogne on August 30th 1915. Unfortunately the Battalion’s war diary, obtained from the National Archives, starts on January 1st 1916 so Frank’s experience before that date is uncertain. However, in January the 11th Essex were in the Line at Potijze in Belgium, so it is likely that they went straight there and fought in the defence of Ypres. Ypres is pronounced ‘Eepra’, but was known as ‘wipers’ to the British Soldier.

Frank was killed in action on Tuesday February 15th 1916 and the war diary records the preceding days. The 11th Essex had been in the trenches around Potijze, with rest periods away from the trenches spent in Ypres. Whether this could be described as rest is arguable as although they were behind the front line the town was constantly shelled and while ‘resting’ they still had to form working and carrying parties.

Frank returned to the trenches for the last time on the 11th. The bombardment was heavy and there were seven casualties that day. The shelling continued on the 12th and they observed an aircraft flying low over the enemy trenches before a gas alarm was called and a heavy cloud drifted towards them. It seems that it was smoke and not gas, but not knowing that and fearing that it was hiding an enemy attack they had no choice but to bravely stand their ground and pour rapid fire into the smoke. There were six casualties that day, but the next day was quieter with only three. The 14th was more eventful, more shelling, two mines2were blown somewhere to their right and the trenches were subject to enfilading – fire from the flank, along the line of the trench - very dangerous. Casualties included three officers and eight other ranks. On the 15th the enfilading continued, their front line was hit by shrapnel shells and they suffered thirteen casualties. It was the shrapnel that wounded Frank. The diary makes a simple statement ‘D Company had Serjeant Major Cannon wounded’ - it was fatal.

He did not die in one of the recognised Battles of Ypres, of which there were three, but rather in the general and bloody defence of the salient3to the east of Ypres. This prevented the Germans from taking Ypres and moving west to capture the British supply ports. By the end of the war 1,700,000 men from both sides had been wounded or killed in this area of Belgium.

Various local newspaper reports record his death and confirm his connection to Pirton. One records two families in bereavement, and notes that one was from the war ‘the sudden death at the Front of Sergt (actually Company Serjeant Major) Frank Cannon whose family had been residing in West Mill for some time.’

The reports that appeared in the North Herts Mail add detail from a letter written by Quarter Master Serjeant, L P Martin. The 13th Essex had been in the trenches for sixteen days and were just about to be relieved, ‘He was just ready to leave the trench when several shrapnel shells burst over him, wounding him and several others. Although his wound was rather serious – he was wounded in the back – it was quite thought he would get to England and recover, but I am sorry to say he died on his way to the dressing station about an hour after he was hit.’ It also confirms that Frank’s brothers, Harry (actually Charles Harry), Robert and Ralph were all serving, and that Ralph was serving in the same Battalion as Frank. His brothers do not have a known connection to Pirton, at least not before the war, although after the war Robert moved to West Mill and worked as a dairyman.

The 13th Platoon Commander, H Aylmer Burdett also wrote to Frank’s wife expressing how sorry he was for her loss.

The Parish Magazine of May 1918 lists some of the subscribers for the War Memorial Shrine and it includes a donation of ten shillings, a substantial sum, from Mrs Cannon of the High Street, presumably his widow.

![[image] [image]](http://i570.photobucket.com/albums/ss147/hwallen/cannon-frank-01v1-jw039-2004.jpg)

Frank Cannon is buried in Potijze Burial Ground Cemetery, Ypres, West-Vlaanderen, Belgium. The cemetery lies to the north-east of the town and holds 584 Commonwealth burials from the First World War, of which 565 are named graves. It is a large space considering the number of burials and with low walls has an unusually open and exposed feel. Now it is surrounded by private housing, but at the time was an area which suffered constant shell fire. It was close to Potijze Chateau, which contained an advanced dressing station and this may be where Frank spent his last hours. His family chose an inscription for his headstone ‘Always Remembered by Those at Home’.

Frank is also remembered on the Hitchin Town War Memorial.

1 John Herbert (b c1883), Charles H (probably Harry, b c1884), Frank (b 1885), Alice (b c1887), Robert (b c1888), Annie (b c1882), Ralph (b c1884), Ida (b c1889) and Cecil V (b 1890).

2 Armies mined under their enemy’s lines, packed them with explosives and blew them up to dramatic affect causing a massive death toll.

3 A salient is an area protruding forward from the rest of the line and therefore liable to attack on three sides.

(Thanks to the Pirton WW1 Project for permission to reprint the above article.)

Alan Fowler

![[image] [image]](http://i570.photobucket.com/albums/ss147/hwallen/alanfowler.jpg)

FOWLER, ALAN

Rank: Serjeant

Service No: 5733161

Date of Death:10/07/1944

Age: 37

Regiment/Service:Dorsetshire Regiment 4th Bn.

Grave Reference X. C. 25.

Cemetery BANNEVILLE-LA-CAMPAGNE WAR CEMETERY

Additional Information:Son of Joseph and Phyllis May Fowler; husband of Emily Mae Fowler, of Swindon, Wiltshire.

Alan Fowler played for Leeds and Swindon before the war. He appeared as a guest for QPR and Watford several times in the early war years.

The following is taken from SwindonWeb:

The true and tragic story of Swindon Town's Normandy hero revealed

Footballers are often said to perform ‘heroics’ on the pitch these days, but very few get to be real-life heroes.

Swindon Town striker Alan Fowler literally became a hero when he was killed in action in Normandy in 1944, but now new research has revealed that Fowler’s tragic story comes with a chilling twist.

In peacetime, Alan 'Foxie' Fowler was an all-round sportsman who, despite being only five-and-a-half feet tall, turned out to be a naturally gifted striker.

He made an instant impression after signing from his hometown team, Leeds United, in May 1934, scoring on his debut in a 3-1 win over Queens Park Rangers at the County Ground.

He went on to be top scorer in three seasons, and ranks twelfth in the all-time list of Swindon goalscorers, netting 102 goals in 224 appearances.

It earned him a place in club historian Dick Mattick’s 2002 book, Swindon Town Football Club: 100 Greats.

“At just 5ft 6in,” explained Mattick, “Alan was small for a striker, but he made up for his lack of inches with speed of thought and good ball control. He was no slouch in the air either, as many of his goals came from headers, where his sense of timing enabled him to beat much bigger men.”

War declared

Fowler would have gone on to be even higher in Town's goalscoring ranks had war not interrupted his career in September 1939, and it was perhaps fitting that he would score the club’s last two goals before hostilities put an end to regular professional football at the County Ground (which was subsequently commandeered as a prisoner-of-war camp).

He got both goals in the 2-2 home draw against Aldershot – the third game of the season, and the last until professional football returned, after the war.

Fowler briefly returned to Leeds to play wartime football, but with a wife in Swindon and with his parents also now living locally (at 7 Leicester Street), he returned to the area to enlist, and found himself in the Dorsetshire Regiment (often affectionately called ‘The Dorsets’).

Footballers were sometimes cruelly labelled ‘D-Day dodgers’ during the war, perhaps because their sporting prowess made them natural trainers, rather than frontline troops.

Indeed, Fowler was a sergeant PT instructor, and neither was he in the first wave of soldiers ashore in Normandy on D-Day, June 6, 1944.

But he would soon see some of the fiercest ever fighting - and experience it first hand.

The Dorsets were part of the 43rd (Wessex) Division, which also included two battalions from the Wiltshire Regiment, and others from the south-west.

He had been born a Yorkshireman, but he would die a West Countryman.

Fowler had already earned praise, long before embarking for France, with the Evening Advertiser later recalling how, in 1941, he “distinguished himself… by saving three men’s lives as well as his own, whilst priming grenades”.

No further details of that incident are recorded, but it’s no exaggeration to say that what happened to his regiment on July 10, 1944 has assumed a kind of legendary status in the annals of British Army action, and Fowler's battalion, the 4 Dorsets, were in the thick of it.

To Normandy

The Wessex Division had arrived in France on June 24, and a little over two weeks later were destined to play a key role in one of the pivotal actions of the whole campaign – Operation Jupiter, which was the breakout after the British finally liberated the strategic city of Caen.

The plan had been to liberate Caen on D-Day itself, but this wasn’t achieved until the day Alan Fowler died: July 10, 1944.

His battalion had already left Caen behind, and were in the front line, south-west of the city, when, at first light on that sultry morning, their orders were to liberate the towns of Eterville and Martot.

This was part of a wider effort to capture the strategic Hill 112 - an operation whose historical importance cannot be overstated.

It was later reported that the Germans, recognising the supreme significance of this one day above all others, remarked: “He who controls Hill 112 controls Normandy.”

No wonder the fighting has been described as “of shattering intensity, even by the standard of Normandy”.

Eyewitness

Sadly, Alan Fowler would not live to see the victory, becoming possibly the first casualty on that fateful day, and probably the most tragic.

The details are revealed in Patrick Delaforce’s Book, The Fighting Wessex Wyverns, although it has only now emerged that the Sgt Fowler mentioned in an eyewitness account of the action is the same Alan Fowler who had played inside-right and centre forward for Swindon Town.

Not untypically of Normandy battles, the assault began with a massive bombardment of enemy positions, the barrage including intensive artillery and heavily-armed fighter planes, capable of bombing.

The story is taken up by Major GL ‘Joe’ Symonds, who commanded the 4 Dorset’s B Company (as quoted in Patrick Delaforce’s book):

“We were very close to the barrage, still in excellent formation. About four fighters [Typhoons] came over, presumably a little late, dropped two bombs in the middle of my company. A number of casualties including Sgt Fowler were killed.”

There can be no doubt that Fowler therefore died as a result of action from the Allies’ own air support (RAF Typhoons), and was a victim of so-called ‘friendly fire’.

Only Fowler’s age in is dispute. Football statisticians claim he was 33, but the inscription on his grave says he was 37. The Evening Advertiser report of his death, meanwhile, put his age at 32.

Controversy

That report is curious – firstly because it did not appear until August 21, nearly seven weeks after the incident, even though other deaths were usually reported within a week.

It also claims Fowler “died of wounds”, when clearly he must have been killed instantly or very soon after the Typhoons struck.

It is also at odds with the certificate relating to his death, which is kept by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. This specifically records that Fowler was “killed in action”, whereas those who died of wounds rather than on the battlefield were usually recorded as such.

The issue of 'friendly fire' deaths has always been controversial, and there could be some suggestion that the true details of Alan Fowler's death were being concealed.

What is certain is that it adds even more tragedy to an already heartbreaking personal story - yet there was another sad postscript to come.

His father Joseph, who was assistant groundsman at the County Ground, is said to have never recovered from the grief of losing his son, and died in 1947.

The true story of Alan Fowler's death surely only adds to what already was a tragedy, but it does not diminish the honour of one footballer who really can be described as a hero.

![[image] [image]](http://i570.photobucket.com/albums/ss147/hwallen/bonass1of1.jpg)

BONASS, ALBERT EDWARD

Rank:Sergeant

Trade:W. Op.

Service No:1898979

Date of Death:09/10/1945

Age:34

Regiment/Service:Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve

Grave ReferenceSec. G. Row K. Grave 11.

CemeteryHARROGATE (STONEFALL) CEMETERY

Additional Information:Son of George and Amelia Bonass; husband of Dorothy Bonass, of Earswick.

Albert Edward Bonass was born in York on 1st January 1912. During his career he played for Dringhouses, York Wednesday, Darlington, York City, Hartlepool and Chesterfield.

Serving in the RAF for two years after four years as a war reserve policeman in London when he was on QPR’s books (35 appearances, 5 goals), he reached the rank of sergeant wireless operator and was a member of the Caterpillar Club having baled out over Manchester from a Wellington aircraft.

He was killed 8 weeks after the end of the war when the Shorts Stirling transport he was the wireless operator on crashed during a training flight from RAF Marston Moor.

According to the booklet “Aircraft Down – Air crashes around Wetherby 1939 -1945” by Brian Lunn and Gavin Harland, in the early hours of 9th October 1945 a Stirling bomber failed to maintain height and crashed onto Tockwith village street. The Stirling LJ622 hurtled along the rooftops for half a mile bouncing off alternate houses. There were some 17 houses hit with little or no damage in between before the aircraft finally broke up. With so many houses damaged by the crash and subsequent fire only one person in them was killed. The village postmaster Arthur Cargill (68) was asleep in the attic of his home and he was trapped by the flames and the attic floor fell in.

- QPR Report Messageboard -

-

- Follow QPR REPORT on TWITTER!

-

-Photos: From the 1880s to the 21st Century - The Bushman QPR Photo Archives

No comments:

Post a Comment